Introduction

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, British foreign policy became tainted with paranoia that India, the jewel in the Empire’s crown, was vulnerable to invasion by Russia through Afghanistan. When, therefore, in 1878, a Russian Mission appeared at the court of the Afghan ruler, Sher Ali, Lord Lytton, the Governor General of India, immediately demanded that Britain be accorded the same privilege.

Sher Ali, who had not actually invited the Russians in the first place and was in the process of sending them away, refused: even turning back a British Mission at the Afghan border. Lord Lytton’s demand became an ultimatum and, on refusal again, Britain declared war.

The First Campaign (November 1878 - May 1879)

Three British Anglo-Indian columns invaded Afghanistan simultaneously.

Peshawar Valley Field Force

To the north, Lt. Gen. Samuel Browne VC, the one-armed inventor of the famous belt, left Jamrud at the head of the Peshawar Valley Field Force: two divisions totalling some 16,000 men. His aim was to take the fortress of Ali Masjid, commanding the entrance to the Khyber Pass, and then to proceed through the pass to Jalalabad

The fort’s commander, Faiz Muhammad, had about 3000 ‘regular’ Afghan army troops at his disposal, supported by some 200 cavalry, several cannon and 600 tribesmen occupying the surrounding hills.

Browne began by sending two brigades off on separate outflanking manoeveurs: both of which unfortunately soon lost contact with the main force, their transport and each other. Undeterred, he ordered the rest of his troops to attack the fort. They made little progress until the Afghans learnt of the outflanking forces and, fearful of this threat, retreated. Browne then advanced through the Khyber Pass and occupied Jalalabad.

Kandahar Field Force

To the South, Lt. Gen. Donald Stewart assembled the Kandahar Field Force, some 13,000 men, at Multan in the Punjab. He then advanced through the Bolam Pass to Quetta, and then on to Kandahar. Although this advance was uncontested, his men found it tough going because of the extremes of both terrain and climate. He reached Kandahar on 8th January 1879 to find Afghan garrison had fled.

Kurram Valley Field Force

Between Stewart and Browne, Major Frederick Roberts VC of the Bengal Artillery, breveted to Maj. Gen. and placed at the head of the Kurram Valley Field Force, advanced from Thal and occupied the Kurram Valley: driving the Afghans before him until he reached their main defensive position, Peiwar Kotal, at the head of Peiwar Pass.

His force comprised the 2nd Battalion, 8th Kings (newly raised and therefore inexperienced); the 72nd Highlanders; 5th Ghurkas; 2nd and 29th Punjabis; and the 12th Bengal Cavalry: some 6500 men supported by 18 guns.

The Attack on Peiwal Kotal

On 2nd December 1878 he attacked Peiwar Kotal, defended by 5000 men under the command of Karim Khan in well-constructed entrenchment’s concealed in pine and cedar forests, dominating the valley 2000 feet below.

Roberts led 1000 of his men on a night flanking attack, with the rest tasked with guarding his camp and making a frontal demonstration in support. The flank attack, led by troops from the 5th Ghurkas and 72nd Highlanders, rushed two Afghan sangars, but then got bogged down repulsing fierce counter-attacks.

The frontal demonstration, however, quickly turned into a successful attack: finding a position where mountain artillery and marksmen from the 8th Kings could fire down on the Afghan camp and baggage lines. This totally demoralised the Afghans: who withdrew, leaving their camp, their baggage, 18 guns and the defences to the British.

Aftermath

With the British columns firmly established in central Afghanistan, Sher Ali realised that defeat was imminent. He first appealed to the Russians for aid and then, when they declined to intervene, fled to Russian-held Turkestan where he died. He was succeeded by his son, Amir Yacub Khan, who, on 26th May 1879, brought hostilities to an end by signing the Treaty of Gandamack. Under the terms of the treaty, Britain withdrew all but a token force to India and The Amir agreed to accept a British Envoy in Kabul.

The Second Campaign (Sept 1879 - Sept 1880)

Major Sir Louis Cavagnari (seated on chair, centre) in Kabul

The British Envoy sent to Kabul was Sir Louis Cavagnari: a franco-irishman who had been Browne’s chief political officer. He, with his staff and a small escort of Guides (25 troopers and 50 sepoys commanded by Lt Walter Hamilton VC), arrived in Kabul in July 1879.

Unfortunately, Afghan feelings against the British were still strong and, on 3rd September, the residency was attacked by over 2000 Afghan regulars from Herati regiments aggrieved that they still hadn’t been properly paid for the first campaign and blaming the British for their troubles.

The Defence of the Residency

Cavagnari was killed in almost the first moments of the attack and, despite intervention from Yacub Khan, who sent a son and three Mullahs to reason with the Heratis, the Residency was set on fire. By midday only 3 Britons and 30 Guides were fit enough to resist.

Determined to finish what they had started, the Afghans brought up two field guns. The brave defenders sortied, rushed the guns and, catching the Heratis by surprise, took them. Unfortunately, sheer weight of numbers prevented them from dragging the guns inside the Residency. Two more sorties achieved no more.

As by now all the Europeans were dead, the Afghans offered quarter to the surviving 12 Guides on the grounds that they were all Moslems together. This was rejected and the 12 Sepoys lined up, fixed bayonets, and charged into the Afghan hoard.

The British Reaction

An Incident in the Battle of Futtehabad, April 2nd 1879: “A risky moment was experienced by Captain Manners C. Wood, 10th Hussars. An Afghan had cut through his helmet. He fell, and was seemingly at the mercy of his opponent, who, being wounded in the right arm, had his long charra in his left, when Lieutenant Fisher, of the same regiment, came up, and brained the Afghan with the butt end of a carbine.” Illustrated London News, 1879 (Author's Collection)

The British were outraged. General Roberts rejoined the Kurram Field Force and set out for Kabul with orders to exact retribution.

With him he had four cavalry regiments, two infantry brigades, and two mountain batteries of 4 guns each: a total of about 6500 men including the Gordon and Seaforth Highlanders; the 5th Ghurka Rifles; Punjab infantry and cavalry; and the 14th Bengal Lancers.

Although Yacub Khan, himself, met the British at the border and tried to persuade them that the massacre was a result of internal rebellion and that order would soon be restored, Roberts determined to press on to Kabul.

On 6th October 1879, he found his path blocked at Charasia by 13 regiments of Afghan regulars led by the Sirdar Nek Muhammed and supported by the usual tribesmen. The British attacked in an uphill flanking manoveur, led by the Seaforth Highlanders and the Ghurkas, and soon pushed the Afghans off the ridge they defended.

Charasia is also significant as the first time that Gatling Guns were used in combat: although their contribution was minimal as one jammed after only 10 rounds.

Roberts entered Kabul a few days later, and held a victory parade on October 13th.

The Occupation

Roberts quickly tried and executed those responsible for the murder of Cavagnari, and established a British military government in and around the city.

Despite his attempts at fair rule, the natives were still restless and by December, stirred up by the Mullah Mushki-Alam preaching jihad all over the country, three Afghan laskars or armies were converging on Kabul. Roberts sent for reinforcements and decided to try and break up the Afghan advance by defeating each laskar in detail: sending out two columns, each about 1000 strong, under Brig. Gen.’s Macpherson and Baker.

Macpherson managed to break up the concentration of Afghans facing him but, due to the incompetence of his cavalry commander, Gen. Massey, could not inflict a decisive defeat.

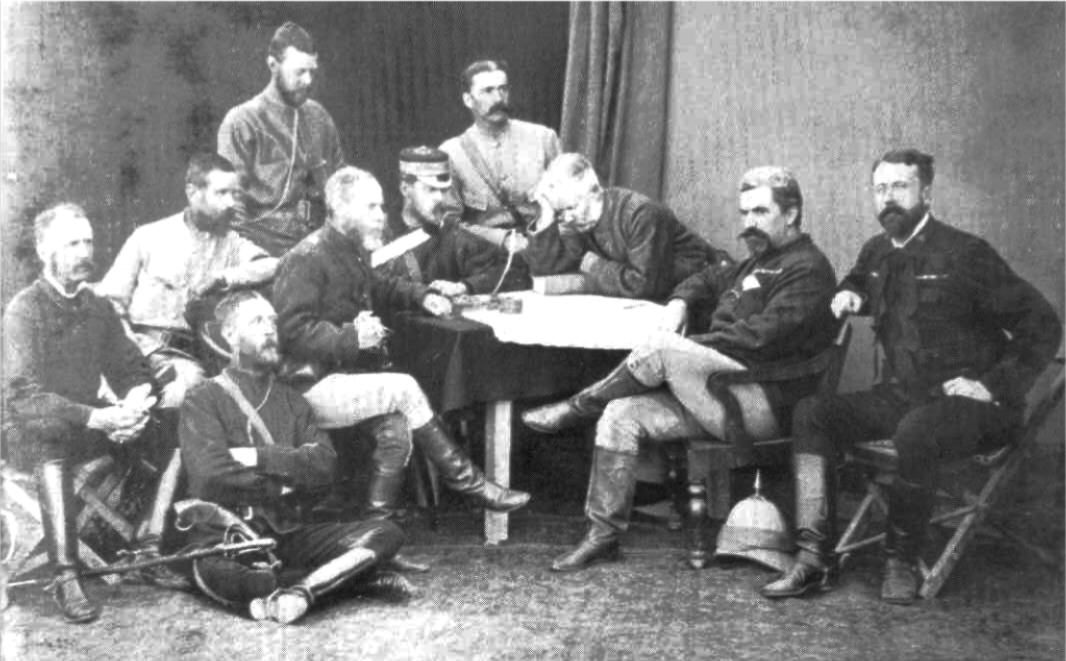

Roberts and his staff in Afghanistan

With the Afghans now consolidating under the banners of Sirdar Muhammad Jan, Roberts adapted his plan to fight their army as it advanced on Kabul. Macpherson would attack the flank, Baker the rear, and Roberts, with his remaining 3000 troops, the front.

Again his plan was thwarted by Massey. By taking an unauthorised shortcut, Massey found his force of 300 troopers and four Horse Artillery 6lb-ders facing 10,000 tribesmen! He retreated hastily and Roberts, four miles away, hearing firing, realised that his plan had failed and led his men “to the sound of the guns”.

Arriving just in time, he covered Massey’s retreat: saving most of the guns through a charge by the Bengal Lancers, who went into action at odds of 40:1. Roberts himself was unhorsed in the savage hand-to-hand fighting that followed, and was only saved from serious injury by a sepoy.

Having rescued Massey, the British retreated rapidly, with Macpherson’s arrival in the Afghan rear preventing the Afghans from following up.

Sherpur

Deciding that he did not have enough men to defend Kabul itself, Roberts abandoned the city and set up camp in the nearby Sherpur cantonments.

The Afghans quickly laid siege and, on 23rd December 1879, launched a series of attacks. The first was repulsed by the modern weapons of the British, but the second, an hour later, almost overwhelmed the British line. Fighting against odds of 8:1, they were only saved by Roberts ordering the 5th Punjab cavalry to leave the cantonments and charge the Afghan rear. The Afghan line crumbled, with 1000 dead left on the field.

With British re-inforcements arriving, Roberts was able to re-occupy Kabul on Christmas Day: and relative peace was restored.

Meanwhile, in London, the government were desperately seeking a way to extricate themselves from Afghanistan: being unwilling to be burdened with the expense of keeping order in such a hostile environment. Eventually they decided to sacrifice Roberts and the memory of Cavagnari to political expediency. Roberts was censured for his severe treatment of the murderers of Cavagnari; Yacub Khan was replaced by his cousin, Amir Abdur Rathman, and a relatively stable and popular regime was established.

The Battle of Ahmed Khel

North Afghanistan was, however, still full of unrest.

On 19th April 1880, a column under command of Lt. Gen. Sir Donald Stewart, marching from Kandahar to Kabul to help pacify the area, was attacked by Ghazi and Hazaras religious fanatics about 20 miles west of Ghazni.

Under their green and black flags, Afghan horsemen swept down on the British flanks, whilst fanatical swordsmen charged the centre. Again, their initial rush was nearly successful: with a squadron of Bengal Lancers routing into the 19th Punjabis and causing confusion. The 59th had no time to even fix bayonets, and it looked as if the issue was in the balance.

However, the 3rd Ghurka Rifles (under command of Colonel Lyster VC) and 2nd Sikhs stood fast and formed square. The British line steadied, and gradually their fire and artillery repulsed the Afghans.

Having won the battle, Stewart then took Ghazni without a shot being fired, broke up another concentration of tribesmen at Arzu, and then, the area being relatively pacified, returned to Kabul where, as senior officer, he took charge and became Commander-in-Chief of the Kabul Field Force.

Ayub Khan

In the North, all was now quite quiet. In the South of Afghanistan, however, near Herat, Ayub Khan, a popular Afghan prince and son of Yacub Khan, claimed the right to rule Kandahar. At his disposal he had a force of about 7500 Durrani tribesmen, ex-regulars from the Afghan army, and a large number of Ghazi religious fanatics.

On 27th July 1880, this force defeated a British brigade, including the 66th (Berkshire) regiment, under General Burrowes at Maiwand, and forced it to fall back on Kandahar with the loss of over 1000 men.

The disastrous (to the British!) battle of Maiwand has been covered in some detail in a previous WI article, but is nicely summarised by Baden-Powell in his Memories of India, published in 1915, when he visited the battlefield during his posting to Kandahar a few months afterwards:

Erected in 1886, the Maiwand Lion stands in Forbury Gardens in the centre of Reading, Berkshire, and commemorates the death of officers and men of the Royal Berkshire Regiment in the 2nd Afghan War (Author's Collection)

“Everything was very much as it had been left after the fight. Any amount of dead horses were lying about, mummified by the sun and dry air. There had been no rain and apparently very little wind since the battle was fought, and the footmarks and wheel tracks were perfectly clear in every direction.

“Lines of empty cartridge cases showed where the heaviest fighting had taken place: wheel-tracks and hoof-marks showed where the guns had moved, dead camels and mules showed the line of the baggage train. Dead men lay in all directions; most of them had been hurriedly buried, but in many cases the graves had been dug open again by jackals. Clothes, accoutrements, preserved food, etc., were strewn all over the place. In one spot the whole of an Afghan gun team, six white horses with pink-dyed tails, had been killed in a heap by one of our shells.

“The British brigade in marching early in the morning had sent out a reconnoitring party to visit the only watering place on the desert to the westward, and this patrol had returned saying there were no enemy there. It was therefore at once assumed that no enemy were in the neighbourhood, but, as subsequently transpired, the patrol had not been to the right place and the enemy were there all the time. That morning a heavy mist hung over the plain and the Afghan army had crossed just in front of the advance of the brigade, neither party being aware of the other.

“Unknown to the British a deep ravine ran in a horse-shoe form almost entirely round the spot on which the brigade was standing. The brigade formed a square to receive the attack, expecting to see the enemy coming across the open, instead of which the Afghans poured down the nullah by thousands unseen, and then suddenly made their attack from three sides at once.

“Some Bombay cavalry, ordered out to charge them, swerved under their attack and charged into the rear of our own men, and the native infantry broke and ran with them through the ranks of the Berkshire Regiment, the 66th. These stuck to their post as well as they could but were driven back, and then held one position after another to cover the retreat of the remainder, but in the end were practically wiped out in doing so. They made their last stand at a long, low mud wall and ditch.

“It was at this spot that one of the men waved his hand cheerily to the Horse Artillery getting their guns away, and cried that historic farewell: "Good luck to you. It's all up with the bally old Berkshires!"

“They were all killed here, and the shortest way of burying them was to throw down the wall on the top of them.”

This was also, incidentally, the battle at which a certain fictional Dr. Watson took the jezzail bullet in his left shoulder that troubled him throughout his long association with Sherlock Holmes.

The Kabul-Kandahar Relief Force

Ayub Khan then laid siege to Kandahar: defended by a well-supplied garrison of 5000 men and 13 guns under General Primrose.

As soon as news of the defeat and siege reached Kabul, Lt Gen Stewart ordered Roberts to form a flying column (to be known as the Kabul-Kandahar Field Force) of one cavalry brigade, three infantry brigades and four mountain batteries. The force comprised 2836 British troops and 7151 Sepoy and Ghurka troops from the 9th Lancers, 60th Foot (Duke of York's Rifle Corps and Light Infantry), 72nd Highlanders, 92nd (Gordon's) Highlanders, 2nd, 4th & 5th Gurkha Rifles, 2nd, 3rd & 15th Sikhs and 23rd, 24th & 25th Punjabis. It, with its 7000 followers, left for Kandahar on 8th August.

Roberts’ column carried minimal baggage with European officers, for example, being restricted to just one pack mule for their personal possessions. Troops carried iron rations only, with other food to be purchased en route.

Conditions were terrible: temperatures during the day hit 43o C (110o F) with fierce dust and sandstorms adding to the misery. By night it was barely above freezing. Despite this, the column covered 305 miles in 23 days, with only one full rest day.

Meanwhile, Primrose’s defenders had continued to hold out: although a sortie against the Afghan gun positions was badly mauled.

On 27th August, communication was established by heliograph with the Kandahar garrison; with a face-to-face meeting with patrols from city a short time later. The relief force finally entered Kandahar on 31st August.

Attack on a baggage train near Koruh, by marauders of the Mangal tribe. Illustrated London News, 1879 (Author's Collection)

Battle of Kandahar

After a brief rest, on 1st September Roberts sortied out of Kandahar and attacked the Afghan army.

With the some of the garrison troops protecting his flanks and the heavy artillery, Roberts again used a combination of demonstration and turning attack to defeat his enemy.

Whilst the 3rd Brigade threatened the key Afghan position on the hill of Babawali Kotal, the 1st and 2nd Brigades carried out the main attack in a turning movement through the village of Pir Paimal. His cavalry he kept to the rear, with the rest of the garrison troops holding the centre in case things did not go to plan.

Battle commenced at 9.30am and, after meeting considerable opposition amongst the village and surrounding orchards, the 1st and 2nd Brigades dislodged the enemy troops after fierce hand-to-hand fighting. Both brigades then advanced to turn the Afghan position on Pir Paimal, and take rest of Afghan army in rear.

The Afghans attempted to form a new line, but the British pressed home their advantage with the 2nd Ghurka Rifles; 92nd Highlanders and 23rd Pioneers storming the Afghan defences in front of their camp.

Ayub Khan fled: leaving his army to disperse pursued by the British cavalry.

Aftermath

Kandahar was the last significant action of the 2nd Afghan War. Ayub Khan disappeared from the scene, and an agreement was reached with Amir Abdur Rahman to the effect that he would not deal with the Russians and, in return, the British would withdraw from Afghanistan and not foist an envoy on him.

The last British troops left Afghanistan in May 1881.

Wargaming the 2nd Afghan War

The Second Afghan War is ideal as a source for wargaming ideas: consisting of a series of set-piece battles and skirmishes within a clearly defined campaign setting.

Skirmish games could include ideas such as the defence of the Residency at Kabul; British pickets clearing the ridges before the start of a morning’s march; an isolated party of British latecomers or re-inforcements being attacked as they try to catch up with the main column; a forage party out scavenging for water or food; or even a band of survivors of Maiwand conducting a fighting retreat.

The set-piece battles include Peiwal Kotal; Charasia; the actions around Kabul; Ahmed Khel; Maiwand and Kandahar.

Campaigns should focus as much on the movement of troops as the battles themselves: with success also dependent on the ability to hold a region or area once taken. It would be challenging to adopt either the British or the Afghan role: with plenty of opportunity for devious character play!

The War also provides a number of interesting “what if?” situations. What if, for example, the Russians had intervened on the side of the Afghans? Or even on the side of the British?

Afghan Forces

Afghan forces were generally a mixture of the ‘regular’ Afghan army and groups of tribal irregulars.

The 37 ‘regular’ infantry regiments consisted of a nominal 600 men each; supported by 16 cavalry regiments (also of a nominal 600 men) and 49 6-gun artillery batteries. The artillery batteries comprised 22 pulled by horse; 18 of mountain guns loaded onto mules; 7 pulled by bullocks; and 2 hauled by elephants.

Regiments tended to be recruited from tribal groups e.g. at Maiwand, 5 regiments were from Kabul, three were from Herat etc.

Regulars carried a variety of weapons: Sniders, Enfields, rifled carbines and even Brunswick and Brown Bess muskets. I usually class them as being armed with muzzle-loading rifles.

As for uniforms: the cavalry dressed in blue or red tunics, with blue trousers and brass helmets or fur caps. The infantry wore black caps, and brown tunics and trousers with red facings. Paying homage to the “devil’s in skirts”, the Afghan army also had one unit of Highland Guard: who wore red and white ‘kilts’ over trousers, white sun helmets, and were armed with Sniders.

The tribal irregulars were armed and equipped as any tribesmen on the NW Frontier: civilian clothing, armed with jezail and khyber knife or sword.

British Forces

British troops wore a mixture of their usual red or blue uniforms and white drill summer uniforms dyed khaki. Highland regiments retained their tartan trews or kilts. Puttees were also used. Headgear was white sun helmets, often worn with a khaki cover.

British/Anglo troops used Martini Henry rifles: sighted to 1200 yards (1098m) but best at less than 400 yards (366m) over open sights. They fired a .450 round that would flatten if it hit bone: causing terrible, shattering injuries. It did, however, have a tendency to overheat and jam, especially with poor quality Boxer cartridges that would break apart in the breech.

British/Indian troops would have been dressed and equipped in a similar fashion, with variations mainly in headgear (caps and turbans instead of sun helmets). It is possible that not all units would have been issued Martini Henry’s, retaining instead Snider-Enfields: although a contemporary print that I have shows the final stages of the battle of Kandahar and depicts a Sikh battalion dressed in khaki and armed with Martini Henry’s.

Bibliography

There is an awful lot of information available on the Second Afghan War. Rather than provide a long list of primary sources, secondary sources that provide a good overview include:

The Savage Frontier (D. S. Richards, Macmillan 1990)

North-West Frontier 1837-1947 (Osprey Men-At-Arms series)

Colonial Wars Sourcebook (Philip J Haythornthwaite, Arms & Armour Press 1995)

Go to Your God Like A Soldier (Ian Knight, Greenhill Books 1996)

I would also recommend a bit of research on the Internet (search under “Second Afghan War” and ignore all the references to the recent Russian invasion of Afghanistan) and the purchase of a descent collection of Kipling’s poetry. Works such as Bobs; Arithmatic on the Frontier and Shillin’ a Day give a real contemporary feel of the conflict.

Finally, many regimental museums have excellent Second Afghan War displays. In particular, I recommend the Ghurka Museum, Winchester (on the hill at the old barracks with another four regimental museums for company), and the museum of the Berkshire Regiment in Salisbury (right next to the Cathedral).